Lessons from Military Operations in Leading High-Stakes Tech Projects

The initial deployment failed. A key API just went down. The client’s feedback on the demo was the exact opposite of what we expected. A senior developer just gave their two weeks’ notice.

This is the reality of managing high-stakes technology projects. It’s a landscape of constant uncertainty, shifting variables, and immense pressure to deliver. In this environment, your team’s ability to execute doesn’t just depend on their technical talent; it depends entirely on the quality of their leadership.

Long before I was the founder of an AI development firm, I was a Commissioned Officer in the U.S. Marine Corps. My job was to lead teams in complex, often dangerous, and always unpredictable environments. The lessons I learned about planning, communication, and execution weren’t abstract theories; they were practical tools forged under the most demanding conditions.

Today, I apply that same operational mindset to leading technical teams. The tools and tactics are surprisingly, and powerfully, universal. Here are some of the most critical lessons from military operations that have become the bedrock of how I lead tech projects.

1. Mission Planning Isn’t About Predicting the Future; It’s About Preparing for It.

A common misconception is that military operations succeed because of a perfect plan. The truth is, no plan ever survives first contact with reality.

The value of the military planning process isn’t the plan itself; it’s the process. It’s a rigorous framework for thinking through a problem, identifying risks, and building contingencies. One of the most critical steps is “wargaming” — where you actively try to break your own plan. We would ask questions like:

What if the enemy doesn’t do what we expect?

What if we lose communication with a key unit?

What is the single most likely point of failure in this plan?

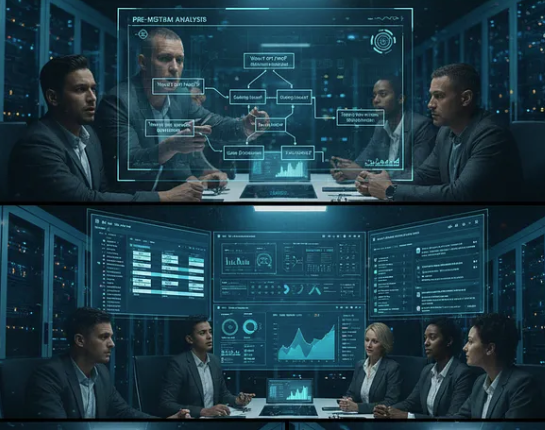

In the tech world, this is the pre-mortem.

Before we write a single line of code, I gather the team and we have an honest conversation based on one premise: “Imagine it’s six months from now, and this project has completely failed. What went wrong?”

The answers are revealing.

“The data from the third-party API was too inconsistent.”

“The performance couldn’t scale to meet user demand.”

“The end-users found the interface too confusing and refused to adopt it.”

By identifying these potential points of failure upfront, they cease to be unforeseen disasters and become anticipated risks. We can then build contingencies directly into our architecture and sprints, turning panic into process.

2. Establish and Maintain a Common Operating Picture (COP).

In a military operation, a COP is a single, shared source of truth — typically a digital map or display — that gives every participant a real-time, identical view of the battlespace. It shows where friendly forces are, where the enemy is, and the status of the mission. Without a COP, confusion reigns, and friendly fire becomes a real danger.

The “friendly fire” of the tech world is siloed teams working at cross-purposes. It’s the front-end team building for an old version of an API, the backend team discovering a critical flaw that marketing is already promoting, or leadership getting a completely different status update than the engineers on the ground.

Establishing a COP is non-negotiable. This isn’t just a JIRA board; it’s a cultural commitment to a single source of truth.

For Development: A well-maintained and universally understood project board (JIRA, Linear, etc.) where the status of every piece of work is transparent.

For Performance: A shared dashboard (Grafana, Datadog) that shows the real-time health of the application in production.

For Communication: A dedicated, disciplined Slack channel where all major updates, blockers, and decisions are documented.

When everyone is looking at the same map, the team can move with speed and alignment, even when the project becomes chaotic.

3. Conduct Blameless After-Action Reviews (AARs).

After every significant mission, we would conduct an After-Action Review. The format was simple, direct, and brutally honest. We would sit down as a team — from the most junior Marine to the commanding officer — and answer four questions:

What was supposed to happen? (The Plan)

What actually happened? (The Reality)

Why was there a difference? (The Analysis)

What will we do differently next time? (The Action)

The most important rule of the AAR is that it is blameless. The goal is not to find who to punish for a mistake, but to collectively understand why the mistake happened and improve the process so it doesn’t happen again. This fosters a culture of psychological safety, where people feel safe admitting errors in the service of making the team better.

This is the exact purpose of a great Agile retrospective or project post-mortem. When a deployment fails or a sprint goal is missed, a weak leader looks for someone to blame. A strong leader asks the team, “What part of our process allowed this to happen, and how can we strengthen it?”

This approach transforms failures from morale-killing events into invaluable opportunities for growth, creating a resilient team that learns and improves with every iteration.

Leadership is the Force Multiplier

In the military, a great leader is known as a “force multiplier” — someone whose presence and actions make their entire unit more effective than the sum of its parts.

The same is true in technology. The most brilliant engineer or the most sophisticated AI model can fail if the team is poorly led. By applying these battle-tested principles of planning, communication, and continuous improvement, you can lead your team through the inherent chaos of innovation and turn high-stakes projects into decisive victories.